One of the things I appreciate most about being a professional writer is having an outlet to process aloud, and share, about the plethora of things I encounter in life. As someone who has been a “deep thinker” for as long as I can remember, writing offers me a way to not only express myself, but also connect with others who may be thinking and feeling their way through the same things. It’s this very idea that has made is so important for me to write books like Self-Care for Black Men: 100 Ways to Heal and Liberate.

As I was making my way through Substack recently, I came across this post from

which stopped me in my tracks. Click the play button to watch the clip as actor Woody McClain discusses navigating being a Black man in Hollywood. Please take the next few minutes to watch this clip in its entirety before moving forward. This is helpful context for the reflections in this post.“I don’t want people to keep perceiving me as this bad person…”

At around the 1:18 mark in this clip you notice that McClain starts to digest and re-experience the story that he’s just told. He’s feeling the weight of the words that have also just fallen out of his mouth, because he is a Black man with dark skin he is most often assumed to be a “bad person.”

I don’t think that many people take the time to acknowledge just how horrific this reality is. Here we have a talented performer, in what sounds like an acting exercise full of his peers, and in this professional environment he is forced to contend with their prejudices and racism. And worse yet, when he turns around and attempts to acknowledge how painful that moment was, everyone responds in jest and pivots.

This is, in part what it means to be Black man living in the west. Our pain? Often ignored. And we are forced to navigate life carrying the burden of the meaning that has been assigned to our skin color throughout centuries. We are forced to contend with the burden of being considered a villainous, big, Black, brute simply because we exist. It is this same prejudice that contributes to the highly violent and carceral response to Black boys and men. We are continuously reminded of how scary we are, or the potential we have to be, just because of the richness of our skin, and the stories concocted and contrived by the mainstream.

This is a daily burden.

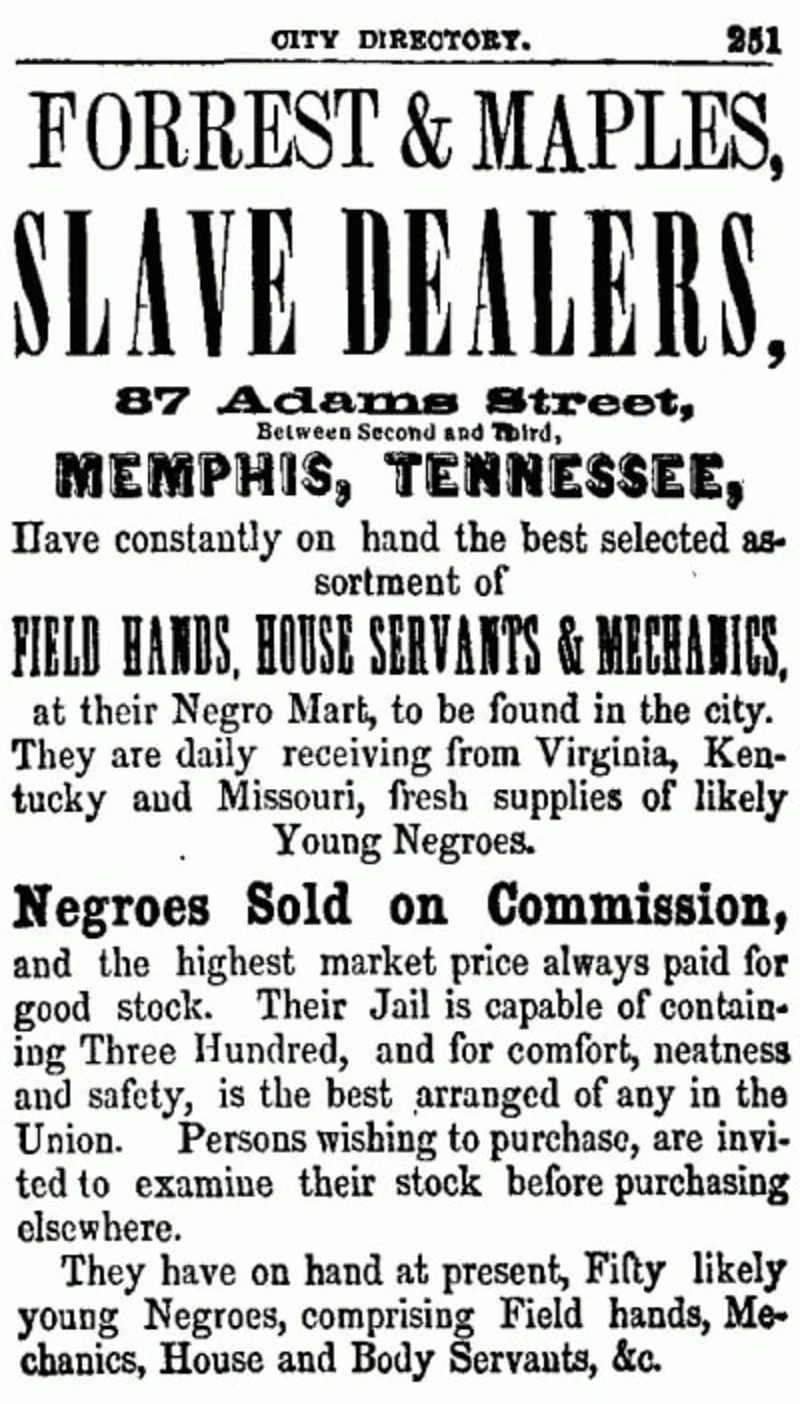

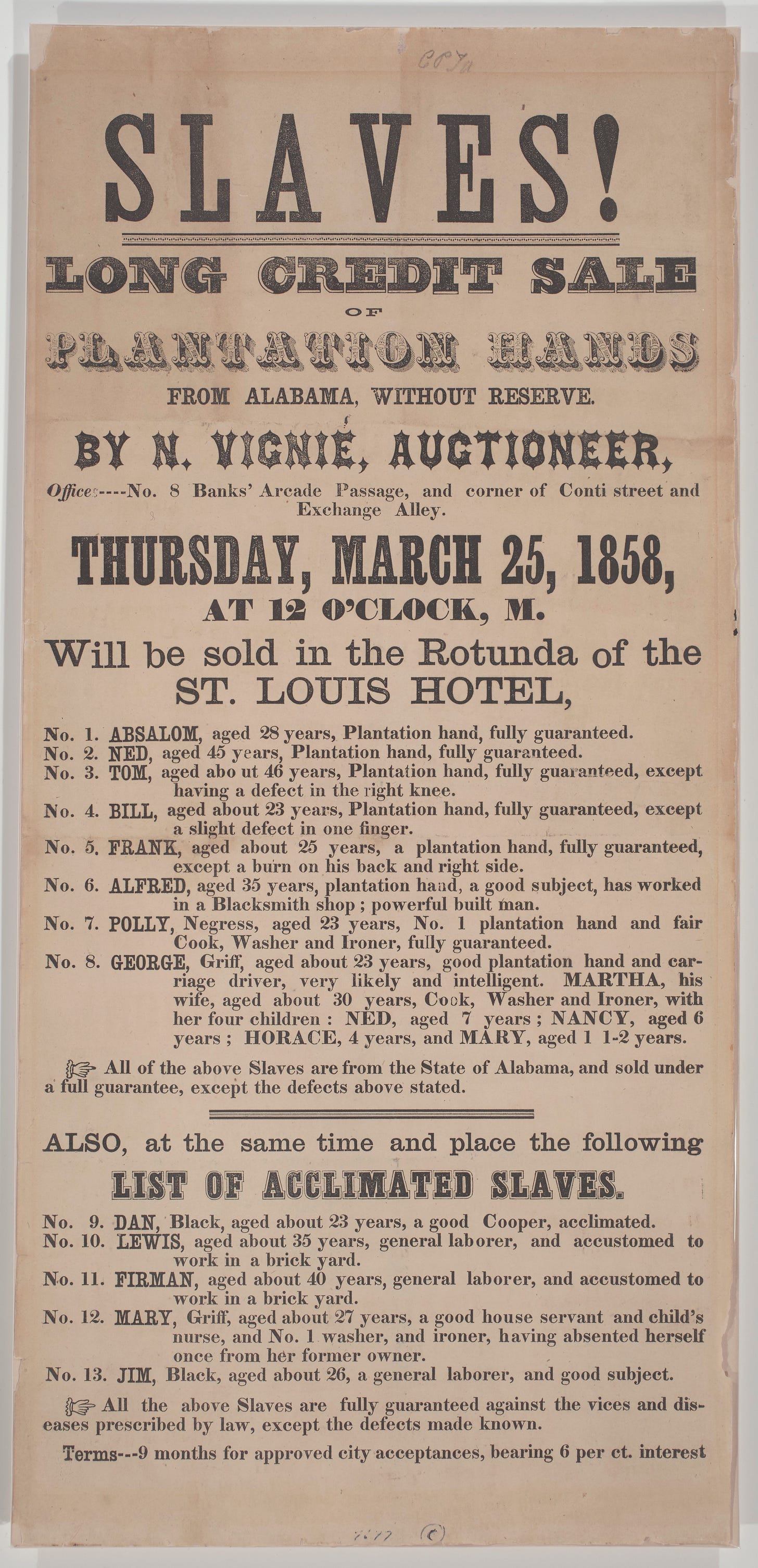

“Good stock.”

The stereotypes of the brutish Black body were born out of the abduction of Africans who were brought to the west as enslaved people. You can witness the nexus of these harmful stereotypes in the advertisements of enslaved people in the early history of the United States. In these advertisements, Black people were described as tools and resources for white land owners to further enrich themselves. In these advertisements there is an interesting phenomenon which you can observe: on one hand you will at times see advertisements of Black men, particularly young “mulatto” ones that reinforce docility and reverence for white people (due to their proximity to whiteness). On the other hand, other advertisements emphasis on the size, strength, and “broad” nature of some Black men, most often the darker ones who were forced to labor outdoors until their bodies fell apart. All of this leaving us with the legacy of colorism that we continue to battle today, even intraracially. Many of these advertisements also make mention of physical flaws that may be of concern to potential buyers, and often speak to the survivability or “acclimation” of enslaved people to reinforce their value, and a hight potential return on investment, for the acquiring human traffickers.

How far away are we from this prejudices and assumptions of Black men today?

If you talk to contemporary Black performers, you’ll hear many stories like the one Wood McClain shared with Cam Newton in that earlier clip. Black men are still reduced to circumscribed stereotypes that rob us of our humanity, whether that’s in acting exercises, casting spaces, or board rooms. I have yet to meet a Black man who has not had to deal with some of these barriers as he navigates life.

What I also find interesting about this clip is how, as McClain shares, Black men respond to these prejudicial burdens. In the clip, McClain talks about how his experience with racism has made him even more conscious of the roles he takes so that he can craft a career that feels more aligned for him. In his choices not only is there spiritual survival, as his mind and soul need to be reflected more fully in his work, but also an intuitive drive towards compensation. Because of the dynamics of race and gender in Hollywood, and in the United States, he can’t help but be conscious of managing the image that he is also putting out in the world, even if that is not his main motivation in the roles he chooses. He, seemingly, has chosen to reject the image of the Black brute, and in doing so, honors his own internal spiritual needs. This also means challenging (for the industry and public) the tropes and stereotypes that are imposed upon him in the first place. In this way, this rejection is compensation for a society’s misjudgment of Black men like him. But at what cost? Why must Black men like McClain, and myself, have to be conscious of navigating a stereotype not of our own creation?

This is a never ending trauma in and of itself.

Consider this, how do you think it would impact you to always been seen as a brute or someone to be feared upon first sight? How might this chip away at your sense of self as you move throughout your day, attending board meetings, picking up your kid at school, or simply driving down the road at night?

This clip made me reflect on how becoming America’s most revered livestock, and simultaneously her most feared boogeyman, chipped away at the mental health, the spirit and soul of my ancestors, those enslaved in a foreign land who, in some ways, were forced to become brutes for the sake of their own survival.

In what ways did they resist? What ways can we still resist now?

As complex as this conversation is, it only becomes more mentally tedious and labored the deeper you go. When does resistance become coping or solely compensation for someone’s else culpability? At what point does this managing, and internal negotiation around discrimination, become overcompensation?

It is here that the lines of mental health are drawn in sand and lined with our blood.

This exploration begs us all to question the ways in which we respond to the dynamics that McClain spoke of in his interview. How many Black men overcompensate by succumbing to the prejudices and perceptions so that they may simply get on with the business of their lives? To what extent have they/we internalized the same messages that our ancestors were revered for on those auction blocks, like strength, ability to endure trauma or the ability to make things manifest by brute force, so that we can have some modicum of protection or semblance of power in our lives? I can’t help but think of all the ways that internalization infiltrates not only our minds but also the dynamics of relationships with our parents, loved ones, and the community at large.

Truthfully, I have more questions than I do answers. And I think its critical that we as Black men, and frankly the entire world, seriously consider how we continue to contribute to the dehumanization of Black people. It is equally as critical for Black men to consider how we invest in, and liberate, ourselves.

I do know that we suffer and have suffered for too long. What I also know is that we’ve persisted, and will also continue to do so. My hope is that the life that endures is filled with more ease, recognition and compassion for the burdens Black men are forced to carry. Ultimately, I hope for full release and relief.

Until then, we carry this burden.